"If You Have"

The new film from Oscar® winner Ben Proudfoot

The untold story of UNICEF

If You Have

Film Transcript, including Visual Scene Descriptions

Opening title card, white type on black

This film was photographed during the COVID-19 pandemic in August 2021, adhering to strict COVID safety protocols.

There were no known cases related to the production.

An elderly Nepalese gentleman stands in his backyard reminiscing about his youth and feeding his cat a saucer of milk, interspersed with old-time film footage of Nepal.

KUL GAUTAM:

For somebody like me, born way up in the mountains of Nepal, a very remote village, five days walk from the nearest bus stop...

Optimism has to be your destiny.

TITLE CARD:

Breakwater Studios and UNICEF USA present…

The film switches to old, black-and-white footage of Nepalese people carrying heavy jugs of water on their shoulders.

KUL GAUTAM:

In those days, you want water? Walk all the way to the river. That was the job of women. Hours and hours spent, my mother, fetching that water. It was so precious.

A photo appears of the elderly man as a young boy, and footage of Kathmandu.

There was no school, no health post. So as a little boy I went to Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal. Wow. Electricity! By the standards of my village, everything was glittering, yeah?

In old, black-and-white footage, a Jeep drives on a road with UNICEF written just below the windshield.

I saw a white Jeep that said U-N-I-C-E-F. UNICEF. UNICEF, what is UNICEF?

TITLE CARD:

A Ben Proudfoot Film

The same elderly man, now seated indoors, speaks to the camera, interspersed with old footage of workers carrying long lengths of pipe on their shoulder toward a rural village.

As I would trek back to my village, I would see along the road porters carrying big bundles of pipes. Pipes for water supply. I said, "Wow!" They were liberating women. UNICEF.

Similar workers deliver construction supplies.

Another occasion, similarly, carrying these big, corrugated iron sheets. Roofing material for schools in the villages.

Nepalese children in the rural villages line up to receive vaccines.

And… vaccines. It was very exciting. A whole bunch of kids going there, lining up for vaccines. Who does it? UNICEF! I thought, “Wow!”

The elderly Nepalese man rolls up his sleeve and shows his own arm scar from the vaccine he received in his youth.

He speaks again to camera, as images from the past 75 years, both of human suffering and human compassion, like nurses caring at a bedside, flash on-screen.

In this world that sometimes seems very selfish and cruel and uncaring, there is an organization that is caring. That focuses on the most vulnerable. And has a track record of success.

Cut to UNICEF emergency supply boxes being delivered through the years, from wooden crates in the 1950s, to a jet airplane being unloaded, to drone deliveries.

The elderly man continues speaking to camera.

So, now as I think about UNICEF providing those things for the last 75 years, it's not just the water and the medicine and the roofing sheets for the school, but really transforming the lives of people.

Hope.

Cut to a shot of the lights of an airplane on final approach in the early dawn in Ghana, West Africa.

The film’s title appears: “If You Have” with a subtitle: “Accra, Ghana. August 2021”

A middle-aged woman does early-morning stretches in her bedroom. Her mattress is on the floor, and there is a child asleep at the foot of it. She says her prayers, and washes her face as she prepares for her day.

FLORENCE NETTEY:

My name is Florence Nettey. I’m a single mother. And a grandmother too. As well.

Florence prepares a large bowl of tofu to sell in her urban Accra neighborhood. She also feeds her grandchild breakfast on the sidewalk outside her cinderblock home.

There is Covid here in Ghana. I am very scared of the virus. People are dying. And I’m looking for my second shot here. I’m looking for it.

Florence speaks directly to the camera in an interview. Cut to footage of Ghana during the pandemic, including deserted streets and health care workers in protective gear. A coffin is lowered into the ground.

Me and a mother in America, we are the same. She’s a human being. I’m a human being. But we the Africans, we lack the vaccine. The problem here - we don’t have enough. That’s why. We are praying for it.

Cut to footage of Florence’s family, including her young grandchildren playing in their neighborhood.

I have to protect myself so that I can take very good care of my children.

Cut back to the elderly man from the beginning, speaking to camera.

KUL GAUTAM:

Well, who cares about those people dying in Africa? Well, let's take care of ourselves. We can do everything by ourselves. The hell with the rest of the world. No sir, we don't live in that world. That world is gone!

Historical footage from epidemics of the past appears, Spanish flu and polio, interspersed with shots of an interconnected, global society: crowded streets, jet planes landing.

When it comes to pandemic, epidemic diseases, smallpox, polio, measles, or COVID-19, no country is safe until all countries and people everywhere are safe. If the disease remains in one part of the world, it is bound to come to your place also.

The film delivers a quick montage of children’s faces from all over the world, followed by footage of scientists and health care workers doing their jobs: looking through microscopes in a lab, packing up vaccine doses, delivering vaccines on trucks and the on the backs of camels, and squeezing oral polio vaccines into children’s mouths.

It's in our hands and power to solve this problem. We have no right to be pessimistic. UNICEF is the largest distributor of vaccines in the world. We have respect, trust, legitimacy, and therefore things that UNICEF can do, not many other organizations can do.

Cut back to the elderly Nepalese man.

My name is Kul Gautam. Former Deputy Director of UNICEF.

OFF-SCREEN:

How did it begin?

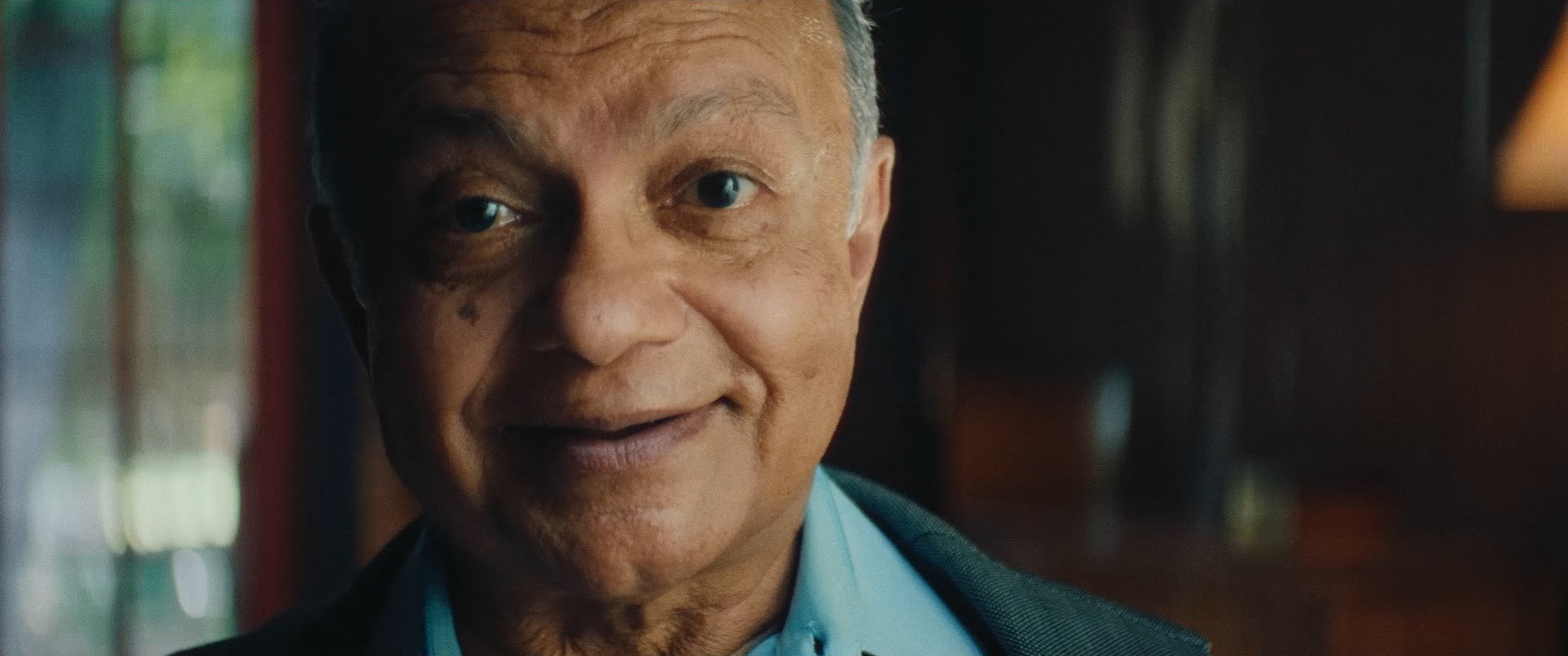

Kul smiles.

KUL GAUTAM:

Ah, that's an amazing and inspiring story.

The scene shifts to street shots of a European town.

A subtitle appears: “Grevena, Greece”

A Greek gentleman, white-haired in his 80s, walks through the town.

DIMITRIOS SIOVAS:

I was born in the town of Grevena in 1937, and I've spent my whole life here.

Cut to old black-and-white photos of him as a child, with his mother and siblings.

We had a quiet life. We weren’t a rich family. We were eight brothers and sisters.

"Always remember to look out for each other." That was my mother's advice, God bless her.

I was five years old. It was a day like any other. Quiet. Peaceful.

Historical footage shows Nazi tanks rumbling over roads and Luftwaffe planes flying over the Acropolis..

And suddenly... every mother went out to call their children back home. It was terrifying. “People are coming to hurt us.”

The Greek man speaks to camera in an interview, interspersed with footage of bombings and goose-stepping boots during the occupation of Greece.

From that moment, what nested in our ears and souls was the word “war.” It was the Second World War and it was the invasion of the Germans in Greece.

Old, black-and-white shows children scavenging for scraps of food in the street and gutters.

We fled the village into the mountains with no shoes and just the clothes on our backs. The hunger. The hunger. Hunger! Do you know what hunger means?

Old newsreel footage shows starving families, emaciated children, people standing in line for food, corpses being loaded into ambulances.

OLD NEWSREEL ANNOUNCER:

Nazi policy becomes extermination by starvation.

They strip the country of its food. With transport disrupted and destroyed, famine kills 450,000 Greeks in 1941-42.

DIMITRIOS SIOVAS:

I didn't understand what was happening. Why should we feel fear? Why should we be hungry? How could children see these things? These are very harsh things for the soul of a child.

But my mother was an optimistic person. “Tomorrow will be a better day,” she said. “We are not alone.”

Cut back to the Greek man speaking to camera.

My name is Dimitrios Siovas. At that time, I was one of the first children helped by UNICEF, but back then it was called UNRRA.

Historical footage shows supply crates stamped UNRRA being stacked and prepped for delivery.

OLD NEWSREEL ANNOUNCER:

The world has heard the cries of pain. At first, help comes from UNNRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency.

Blankets are being handed off of trucks, and children eat bowls of food.

DIMITRIOS SIOVAS:

It was life. From having nothing, we began to have milk, fish oil, food. I really liked peanut butter. I was crazy about it!

Photos of Dimitrios as a young man appear, playing guitar with friends, as well as footage of Greek people celebrating the end of the war.

Young people started to dream. They offered hope for a better future.

OLD NEWSREEL ANNOUNCER:

The wounds will slowly heal, laid over by the scar of time.

DIMITRIOS SIOVAS:

What traumas our souls have sustained, they can't be treated. They stay imprinted in your soul. They can of course teach as well.

Dimitrios today smiles at the old photos from his youth. He says, “Where did you find these photos? This is with my wife.” Cut to photos from his wedding, with his children, from his job.

And we proved it over the course of our lives. I had a full life. I spent my life doing things for other people. I became a doctor. And I became mayor of Grevena, my beloved town. It was very important to give to children what UNRRA gave to us.

Dimitrios speaks to camera and walks around his hometown today.

Always remember to look out for each other. We are not alone in this life.

Cut back to Kul, the elderly Nepalese gentleman, speaking to camera, interspersed with black-and footage from the aftermath of World War II, including the formation of the United Nations.

KUL GAUTAM:

In human history, great crises have come. Great wars have come. Periods of great disappointment, despondency. Hopelessness. But humanity has always risen. After the war ended, peace came. The UN Charter was signed. UN came into existence. Then the question of what do we do with UNRRA?

We still need to provide a lot of relief and rehabilitation. They said let's disband UNRRA, and they created two organizations. One was to deal with the millions of refugees. And then let's establish another organization called UNICEF that will deal specifically with children.

Cut to old footage of Danny Kaye dancing comically with local women in Africa.

OLD NEWSREEL ANNOUNCER:

Actor and comedian Danny Kaye.

KUL GAUTAM:

Danny Kaye became UNICEF’s first Goodwill Ambassador.

Cut to photos and footage of other UNICEF ambassadors.

Later on, many other illustrious stars. Harry Belafonte. Pele, the great football star. Audrey Hepburn. Audrey Hepburn was the most beautiful, the most elegant, the most famous, the most—anyway, long story. Sorry, I made it too long.

They were able not only to mobilize money, but to mobilize public opinion, public sentiments. The sense of solidarity!

Danny Kaye testifies in front of a committee sometime in the 1960s.

DANNY KAYE:

If we, the so-called adults of the world assume the responsibility for children throughout the world, then perhaps our children can live in a more healthy, happy, and peaceful world.

Cut to historical footage of a jack-o-lantern and children holding up UNICEF coin collection boxes.

KUL GAUTAM:

The appeal was so powerful. UNICEF USA was the pioneer. And then USA adopted Trick-or-Treat.

CHILD IN COSTUME:

Trick-or-Treat! Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF!

Children trick-or-treat door-to-door, including at the White House with first ladies Barbara Bush and Lady Bird Johnson.

KUL GAUTAM:

Made it nationwide, and Trick-or-Treat mobilized millions of dollars over time. That became the backbone of UNICEF's funding.

Cut to newsreel footage of the 1965 Nobel Prizes being awarded, with audiences applauding.

Then in 1965, the Nobel Committee decided to award UNICEF the Nobel Peace Prize. So that was the highest honor that one could get. Can you get any higher than the Nobel Prize?

Cut back to Kul, speaking to camera.

Yes you can. We'll come to that.

The scene shifts to laundry drying outdoors on a line in Accra, Ghana. Florence gives a child a bath outdoors.

CHILD OFF-SCREEN:

Ma!

FLORENCE NETTEY:

I'm coming!

Florence Nettey speaks to camera about growing up. Cut to photos of her as a younger woman.

My dad. He used to call me Nightingale. That’s why he named me Florence. He used to tell me, “In the future, you will be a nurse. Just like Florence Nightingale.” That was my dream.

Florence looks straight at the camera.

But... my dream didn’t come true. It’s a long story, about love.

Cut to footage from the time of Florence’s youth, Ghanian people working by the seashore at a fish market.

I used to accompany my mom selling fresh fish at the markets. That’s where we started, me and Joshua.

Cut to old photos of Joshua, smiling. Florence smiles as she remembers him.

A very cute man. Nice. Calm. And very gentle. I used to trouble him. Oh, I used to trouble him a lot. But he loved me, so we got married. We had ten children. Ten!

He was an account clerk with a school. One day, somebody from school came and told me, “When your husband came to work, he was not feeling well. They have sent him to the hospital.”

Florence looks crestfallen as she recalls the time.

So I rushed there… Pneumonia… He died.

Florence, in the present day, slices bread into a bowl, going about her daily work. Her grandchildren watch her intently and with curiosity.

If you don’t have money and you get sick... That’s why we are praying for the vaccine.

The scene shifts to the front of an office building in Accra, Ghana. A large blue sign over the door reads “UNICEF House.” The sun beats down at midday, and a security guard wipes sweat off his brow.

DR. PRISCILLA WOBIL:

Ghana is a very hot country. Scorching hot.

A woman speaks to camera. She wears glasses and a khaki vest with a blue UNICEF logo on it.

UNICEF HEALTH SPECIALIST:

When it comes to vaccines, the sun becomes our enemy.

Inside one of the building’s conference rooms, two UNICEF staff members are meeting. There is a whiteboard with vaccine delivery statistics written on it.

The very moment you leave the vaccines in the sun, I can tell you: you will lose everything. We need specifically to use the UCC. That's the ultra-cold chain.

The woman in glasses speaks again to camera.

DR. PRISCILLA WOBIL:

I'm Dr. Priscilla Wobil, and I work with UNICEF Ghana. In the mid-‘70s, vaccines had to be distributed widely across the world and maintained at a particular temperature. So, UNICEF and other partners had to build a global cold chain.

Cut to historical footage of vaccine delivery in the 1970s. Ice gets packed around wooden crates, and photo sappear of the design blueprints for an early cold box to carry vaccines while maintaining low temperatures.

The first cold box was a wooden box. The Luxembourg cold box. It was first tested in Ghana, and it worked! It worked. To ensure that the vaccines that are manufactured reach every child, everywhere.

Cut to 1970s images of global vaccine delivery to remote areas, cold boxes being loaded onto helicopters, loaded onto trucks, children in remote Amazon villages getting vaccinated. More modern images appear, including COVID vaccine deliveries through the COVAX initiative being loaded and unloaded from cargo jets.

So the immunization cold chain system that was built to immunize children is now the same system that is being used to vaccinate the world against COVID-19. COVAX, the coalition of partners that have come together to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines are manufactured and delivered equitably to all countries, quickly.

The scene shifts back to outside Florence’s home. Her family is gathered in the alley by her home in the afternoon, and Florence’s granddaughter, 5 or 6 years old, sits in the center and begins a story.

FLORENCE NETTEY:

Story, story, story.

Florence and the children listen intently to the story.

FLORENCE’S GRANDDAUGHTER

Once upon a time... there lived a man. And coronavirus. Coronavirus came to enter the man, and the man died. One day, one day, a virus killed everybody in the world. He said that all that things is for me now in the world.

Florence shows the children how a mask can help protect them. The children watch her and learn.

FLORENCE NETTEY:

She said, "The virus takes over the whole world." You are sitting here without a mask, you need to put on a mask to protect yourself and to protect your friends too.

Cut to a street vendor in Accra selling masks from a cart, and street scenes of life in Ghana with people going about their lives.

STREET VENDOR:

Face masks! Face masks! Face masks!

DR. PRISCILLA WOBIL:

These are teachers, fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters. What happens when they are no longer alive?

The scenes are interspersed with health workers putting on protective suits, masks and goggles. They cinch the gear tight to prevent contamination.

Here in Ghana, less than 3% of the population have been vaccinated. Less than 3%.

The health workers ride in the open back of a pick-up through the streets of Accra. A box between their legs reads “Body Bags.” Cut to images of them in a morgue, placing a body, wrapped in bag, into a coffin. Now in a field, they lower the coffin into an open grave. They begin shoveling dirt into the grave. Cut to images of them removing and burning the protective gear.

Fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters. Here in Ghana, we are in the early stages now of this pandemic.

Cut to Kul Gautam, the Nepalese gentleman, speaking to camera.

KUL GAUTAM:

One crisis after another crisis, humanity has survived. Why? Because we have had inspiring leaders, inspiring teachers, inspiring personalities, who have shown us that the problems can be overcome.

In 1980, UNICEF got a new leader, James Grant.

Cut to news footage from 1980, with James Grant on a news program.

NEWSCASTER:

James Grant, Executive Director of the United Nations Children's Fund, or UNICEF.

KUL GAUTAM:

He sent out a message to all UNICEF staff all over the world.

James Grant looks straight to the news camera and speaks.

JAMES GRANT:

13 million children die, two-thirds of whom could be preventable.

Kul Gautam continues to camera. A montage of images of children from all over the world accompanies his words.

KUL GAUTAM:

Why were they dying? Because they don't have the simple vaccination, which is very cheap, easily available in US and Europe, but not in poor countries. If we were to immunize all the children of the world we could save a lot of lives.

James Grant speaks on another old news program.

NEWSCASTER:

In 1982, Grant launched a child survival and development revolution.

KUL GAUTAM:

He said by the end of the decade we should reach—

JAMES GRANT:

Must reach 80%.

Cut to old, black-and-white images of children crippled with polio, on crutches. Also, footage of vaccination campaigns through the years, including UNICEF trucks carrying vaccines over dirt roads to remote areas.

KUL GAUTAM:

—80% immunization. Eradicate polio, eradicate diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, tuberculosis. A child survival revolution all over the world. We'll mobilize international support, make it a high priority. Do it on a massive scale. Sounds like a good idea, if it could be done.

Cut to two boys in present day, playing basketball in front of ancient ruins, trees and high mountains in the background.

A subtitle appears: Antigua, Guatemala

An elderly gentleman with a raspy voice orders an ice cream cone from a street vendor in the plaza.

AGOP KAYAYAN:

I just wanted to tell you about my voice. I have half the vocal chords you have. That's smoking!

He speaks directly to camera, smiling.

My name is Agop Kayayan. I was the UNICEF Program Officer in Guatemala. I promised Mr. Grant that I wouldn't smoke anymore. Jim Grant. He was my guru. My professional father.

Cut to an old photo of Agop and Jim Grant together long ago. We cut back to Agop today, walking alone in the park and feeding pigeons.

One morning, I'm in the office and I get a phone call. Mr. Grant is on the line. He says, “Agop, I met the president of El Salvador.”

Agop tugs at his hair in mock exasperation.

And I thought, “He does not call because he met the president of El Salvador. There's something coming.”

I was the representative for seven countries and three of them were in civil war.

Cut to old newspaper headlines, describing civil wars in Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador. Old news footage from that time shows buildings burning and street battles in El Salvador.

NEWSCASTER:

El Salvador, a country no larger than Wales, is torn by civil war and terror.

Agop speaks to camera again.

AGOP KAYAYAN:

Grant asked the president of El Salvador if he was vaccinating children. His answer was, “Mr. Grant, you don't understand. My country is at war…”

Cut to images of fighting, military cannons, people turning over cars in the streets, throwing Molotov cocktails, women and children crying.

“…The vaccinators do not want to go into areas where it was dangerous.”

If you don't vaccinate, children and women are paying the price of the war.

Agop speaks directly to camera.

So Jim says, “Agop, you are going to do it. Stop the war.”

I couldn't say no to him. So I went to the Archbishop in San Salvador. I just said it very straight, “Monsignor we are proposing a truce so that children could be vaccinated.” And he said, “I don't think it's going to work. We have tried many times, truces. I don't see why they would accept it from you.” And, you know, what argument can I give the man?

So I said okay, you know what, though? Maybe because of children they will accept.

A montage of armies fighting, soldiers running, guns firing, getting more chaotic as it goes. Then suddenly, everything goes quiet. There are images of quiet, peaceful villages. A single child’s voice sings softly.

You see, UNICEF had the trust of government people and the guerrilla. Credibility. You build it. Brick by brick. You know, you do things right thousands of times and then people say, “these guys we can trust.”

Both sides, guerilla and army, both sides accepted our proposal.

Both sides cease fighting. Young Salvadoran children appear, who will soon be getting vaccines.

Put down the guns and provide full service to children. I was jumping of happiness.

Agop laughs out loud at the memory.

Yes, yes, I did. Like, I was happy. Yes.

Cut to scenes of children receiving vaccines, including one child being given a vaccine by the president of El Salvador.

And so every year, twice, for two days each time for six consecutive years the war stopped completely. Each time, more than 400,000 children were vaccinated against five deadly diseases.

Cut to a Salvadoran news conference from that era with Jim Grant.

JAMES GRANT:

For the very first time in history, war has been stopped for children.

Agop speaks to camera today.

We called it “Days of Tranquility” for a good reason.

The scene shifts back to Kul Gautam’s interview.

KUL GAUTAM:

Now, we have shown proof that it can be done. How can we sustain it? How can it improve it? And saving lives only one part. What's the point of saving them if you cannot improve the quality of life? It is not just the quantity of life, it is the quality of life. What do we need to do for the quality of life?

A scene repeats of the 1965 Nobel Peace Prize presentation, with the award being handed to UNICEF’s Executive Director.

Remember I asked, “Can you get any higher than the Nobel Prize?” Well, I'll tell you the whole story.

We see footage of the United Nations from the late 80s.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted in 1989.

Audrey Hepburn, in front of the UN Assembly members in 1989, reads from the Preamble to the Convention.

AUDREY HEPBURN:

Every child shall enjoy the following rights.

Cut to a montage of children, many of them speaking up for their rights.

KUL GAUTAM:

They have a right to survival. They have a right to their name. They have a right to health, education, to be protected from harm, from violence, abuse, exploitation. Forever.

And Jim Grant said, “Okay now, call for a world summit for children.”

Cut to news footage from 1989, with a montage of world leaders from the time.

NEWSCASTER

This weekend, when more than 70 of the world's leaders sit down together here in New York, it will be the first time a world summit for children be held.

Many children attend the summit, making statements into microphones. They sit at tables with nameplates showing their home countries. They stand and wave with the world leaders.

KUL GAUTAM:

From north and south, east and west, Asia, Africa, Latin America, Europe. That became the largest summit in the history of humanity, and it was a tremendous success.

Kul speaks to camera.

So, there you see, UNICEF followed the principle that said children should be at the center of humanity. Because they are the future of humanity.

Cut to a dusk scene of the skyline of New York City, the east side of Manhattan. The United Nations building is in the center of it all.

Subtitle: New York, USA

A gentleman in a suit sits in an office and speaks to camera.

CORNELIUS WILLIAMS:

If there's a devil chasing you, would you stop?

My name is Cornelius Williams. Associate Director, Child Protection.

As he speaks, cut to quick scenes of modern life, technology, juxtaposed with global mountains and villages.

Since early 90s, the world is now a more complex place. In high income countries, in low-income countries, everywhere.

Cut to a montage of UNICEF delivering supplies via motorbike on dirt roads, setting up water tanks and refugee camps, leading discussions with community members.

At UNICEF, we are on a mission. We work in over 190 countries. We are the partners of governments.

The scene shifts to crisis imagery: climate change, wildfires, hurricanes.

When there's that devil chasing after us, the dark side of humanity.

Cut to Afghan people running down the tarmac after a cargo jet.

NEWSCASTER:

Panic and pandemonium at Kabul airport…

CORNELIUS WILLIAMS:

We owe it to those children.

Cut to children at a climate protest, holding signs and chanting.

CHILD TESTIFYING:

Because climate change has had a major impact.

CORNELIUS WILLIAMS:

This is not a job in a cigarette factory. It's not a job in a bank. It's about humanity.

Cut to imagery of UNICEF’s work: project leaders laying out maps, robots retrieving crates at a huge supply warehouse, drones lifting off the ground.

UNICEF today, we have the technical capability, the infrastructure, and the knowledge to continue to make a difference for children. We have to roll up our sleeves and do it.

Cornelius speaks straight to camera.

Nothing stops us. Nothing. Would you stop?

Cut back once again to an early morning in Florence Nettey’s home. She’s just waking up and rising from bed. It’s still dark outside.

FLORENCE NETTEY:

Yes. I’ve been doing very hard work because of my children. And I’m proud God has seen me through. Five of them have been to university. Yes. Very proud.

Cut to her family and grandchildren smiling, eating tofu that she’s cooked in the street. Also, portrait images appear of the people in her community.

So now, I just look after the children and my community. Look after them well. Even though I’m a single mother, I have to give them everything they need. Everything. I love everybody. I love everybody. Everybody in this house. The people in my community. Anything at all you need, when you ask and I have, I will give you. And that’s why I want to work. So that I can provide every day.

Florence walks the streets of Accra, selling tofu. People purchase and eat it, happy but maskless.

But I’m very scared. Scared of the virus. I hope the world sends the vaccine, so that they will protect the people of Ghana. It will protect the people of Ghana. That’s my prayer.

Florence speaks directly to the camera.

Because, if you have, you have to give.

Cut back to Kul Gautam. As he speaks, footage appears of small villages high in the mountains of Nepal.

KUL GAUTAM:

I recall going to the villages of our neighbors. Walking, walking, walking up and down the hill. When the sun is about to set in the evening, you just go and knock on people's door and say, “Look, the night is coming, we are on our way. Would you be kind enough to let us stay?” They will let you stay.

Various Nepalese people, smiling and welcoming, cook a meal and prepare coffee.

You stay there overnight. And then, early in the morning, you start walking. Today as I look back I say, “Oh my God! The generosity of the people.” They had so little, but they shared. If you have generosity, if you have trust, if you have a sense of solidarity, optimism is your destiny.

Kul speaks directly to camera.

We are luckier than all of our predecessors. We now have the technology. We now have the communications capacity. We can reach everybody! Especially now. It's a fact of life. You are not safe until the whole world is safe. That is the key.

Cut back the image from the beginning of the film, with the tiny lights of a plane coming in for a landing.

No matter how powerful and how rich you are, we live in an interdependent world.

The plane touches down in Ghana, and crates of vaccines are offloaded. They’re transported and kept cold and inspected by UNICEF workers. Then, cut to Florence, in her mask, walking purposefully through the town, as if on a mission. At the same time, coolers of vaccines are driven through town in a pick-up truck, arriving at a health center.

Children should be everybody's business. Film stars and rock stars! Presidents and prime ministers and kings!

Quick, flash images appear of UNICEF ambassadors, like Katy Perry, Jackie Chan, Pink, George Harrison and BTS. Also, images of world leaders. And then Kul points directly to the camera.

And they should be your business.

Cut to historical footage of Danny Kaye’s speech again. As he speaks, Florence arrives at the health center. Vaccine vials being are being lifted out of coolers. Interspersed are portraits of children smiling all over the world, including Florence’s grandchildren.

DANNY KAYE:

That if we, the so-called adults of the world, take on the world's problems of children, I think perhaps the world would be well on its way to understanding itself a little better, and perhaps our children can live in a more healthy, happy, and peaceful world.

At last, Florence gets the vaccine she’s been praying for.

TITLE CARD:

UNICEF is rushing to deliver billions of vaccines globally to end the pandemic once and for all.

As the world’s 2.2 billion children emerge from the pandemic, UNICEF perseveres in its relentless work on their behalf, continuing to serve as a symbol of optimism for humanity.

CREDITS ROLLING

Support UNICEF's Work

You can help UNICEF, funded entirely by voluntary contributions, continue to make the lifesaving impact you see in the film.

$43 could protect 200 children from polio

$51 could provide measles vaccines for 50 children

$58 could fully vaccinate one child for life

$98 could provide safe water and hygiene kits for one family in an emergency

Or Give Any Amount Here

You can also get involved by hosting your own screening of “If You Have.” Contact: hello@unicefusa.org

For press inquiries, please contact: media@unicefusa.org For more information, please contact: events@unicefusa.org

Executive Producers

Orlando Bloom

Sofia Carson

Lucy Liu

Wendy Serrino, Chair

Sippi & Ajay Khurana

Martha & Adam Metz

Wendy & Frank Serrino

Elena Marimo Berk

Landry Family Foundation

Newmarket Capital

Kerry & Brendan Swords

Bill & Cindee Dietz

Susan Littlefield & Martin Roper

Christopher, Thomas & Peter Roper

Tina & Byron Trott

About the Film

“If You Have,” the inspiring documentary from Academy Award®-winning documentary director Ben Proudfoot and Breakwater Studios, celebrates 75 years of UNICEF’s lifesaving work around the world as told through the eyes of those who were there — whether as children being saved from starvation after World War II or as staff tasked with pausing a Central American war to continue a vaccination campaign.

Mixing rare historical footage with in-the-moment filmmaking across four continents, “If You Have” also captures UNICEF’s race to vaccinate the globe against COVID-19 during the height of the pandemic. Since the documentary’s 2021 filming, UNICEF and its partners successfully delivered their one billionth dose of COVID-19 vaccine and are looking to deliver billions more doses by the end of 2022.

To host your own screening of "If You Have," please contact: hello@unicefusa.org

Making the World Better for Every Child

Over eight decades, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has built an unprecedented global support system for the world’s children. UNICEF relentlessly works day in and day out to deliver the essentials that give every child an equitable chance in life: health care and immunizations, safe water and sanitation, nutrition, education, emergency relief and more.

UNICEF USA advances the global mission of UNICEF by rallying the American public to support the world’s most vulnerable children. Together, we have helped save and meaningfully improve more children’s lives than any other humanitarian organization.

Stay up to date on UNICEF's work: