A Path to Protection for Uprooted Kids in Mexico

Mario from El Salvador is one of 1,065 migrant and refugee children and adolescents whose cases were supported by UNICEF Mexico at the southern border. For World Refugee Day, a look at what that means and why it matters.

This is a story about a teen from El Salvador who ultimately found safety and protection in Mexico with UNICEF’s help.

It is a story that speaks to the complexities of migration and displacement in Central America; the multi-faceted nature of UNICEF’s efforts to meet the needs of vulnerable children caught in that plight; and about how UNICEF works to make sure kids know their rights and that those rights are upheld.

Mario (name changed) was 16 and suffering from daily harassment and threats of violence from local gang members when he fled El Salvador with his uncle in late 2017. His mother supported the decision, but stayed behind.

Murals at the Guatemala-Mexico border offer hope to migrants seeking safety and a better life: "Nothing on earth can stop us." "With the inclusion and protection of immigrants, we all win." © UNICEF USA/Dineen

Mario and his uncle crossed into Mexico at Tapachula, in southeastern Chiapas State, a main entry point into the country for migrants and refugees coming from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Arriving without documentation, they were immediately detained by migration authorities and placed in separate areas of Siglo XXI — the largest migrant detention facility in Latin America, with space for 960.

Brenda Hernández met Mario during one of her weekly visits to the center. As UNICEF Mexico‘s Child Protection Officer in Tapachula, the visits are a major part of the job: to identify children and adolescents who are being detained, and then inform the local child protection authorities who can then work to place them in a shelter. Detaining any person who is under age 18 is prohibited under Mexican law.

Two teens from Central America walk out of an open-door shelter for unaccompanied migrant adolescents in Tijuana, Mexico. UNICEF is preparing to open two new field offices — one in Tijuana, the other in Tapachula in Chiapas — to better assist government efforts to protect the rights, safety and well-being of migrant children. © UNICEF/UN0284775/Bindra

Mario had been in the center for a few weeks when Hernández intervened on his behalf. After helping to secure his release to a shelter for migrant children, she also helped persuade government officials to consider a joint application for asylum for Mario and his uncle.

Combining their applications helped ensure that the facts of Mario’s situation — his life back home, living under constant threat of gang violence — would be fully considered. Hernández also advised the child protection authorities to reach out to Mario’s mother in El Salvador to obtain the documentation needed to prove that uncle and nephew were related (they have different surnames).

Child protection officers like UNICEF Mexico's Gema Jiménez work to make sure migrant and refugee children — accompanied and unaccompanied — are getting the care and protection they need. "If I see that something is not right, I just want to do something about it," Jiménez says. "I cannot stay quiet.” @ UNICEF USA

“This is what we mean when we say UNICEF provides technical assistance, advising the local actors who are in charge,” explains Gema Jiménez, a Child Protection Officer for UNICEF Mexico who spoke to Hernández at length about Mario’s case. “This assistance is needed, as the number of unaccompanied children entering Mexico has greatly increased.”

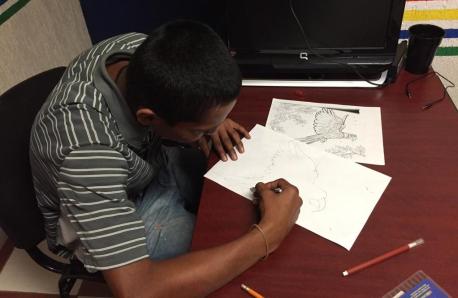

It took about a year, but eventually both Mario and his uncle were recognized as refugees by the Mexican government. This means the two can stay permanently in Mexico; they can live anywhere in the country; they can get jobs and health care and other services available to Mexican citizens, without fear of being deported. They now live together in a rented room. The uncle works temporary jobs under a government-sponsored work program; Mario has been attending a government-run school for migrant kids. He recently completed the 8th grade and is getting ready for high school. He is also back doing what he enjoys most: drawing comics.

Since Hernández has been working in Tapachula with UNICEF, she has helped more than 800 migrant and refugee children and adolescents, both accompanied and unaccompanied. More than 250 have received similar support from UNICEF staff based in Tenosique, in Tabasco State.

There is a significant backlog with the asylum cases, and so [UNICEF Mexico Child Protection Officers] work to bring the most urgent ones to the [Mexican] government's attention.

“There is a significant backlog with the asylum claims, and so I work to bring the most urgent ones to the government’s attention,” Hernández says. “I am glad to have been able to play a supporting role in so many cases over the last year or so, but there are still so many children who need our help. That is why we’re opening two new field offices — one in Tapachula [at the southern border] and one in Tijuana [northern border] — so UNICEF can have more people on the ground doing this work.”

Migrant children and families at the Mexico-Guatemala border in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico. © UNICEF/UN0278802/Bindra

A top priority for UNICEF as part of its ongoing response to the needs of migrant and refugee children in Central America is to keep families together. UNICEF advocates for and helps develop care options as alternatives to detention— such as open-door shelters where children can stay safe and get services, and placement with foster families or in group homes where unaccompanied children and adolescents can live together with adult supervision.

UNICEF provides technical assistance to Colibrí, an open-door shelter for unaccompanied children operated by the government and located in Villahermosa, in southeastern Tabasco state. UNICEF also provides psychosocial support materials and manuals to a number of shelters run by the Catholic church.

As Jiménez points out, UNICEF and other organizations are closely supporting an end to detention of migrant children in Mexico. Under a new law enacted in Dec 2014, all children in Mexico have the same rights regardless of nationality or migration status. Those rights include the right to live a life that is free of violence; to be part of a family; to access health care, education and recreation, among other rights and privileges.

“The Mexican government and people have been mostly welcoming towards the thousands of children and families crossing their borders every day,” Paloma Escudero, UNICEF Director of Communication, said after a two-day visit to Tapachula in February 2019. “Whether these children stay in Mexico or head further up north, it is crucial that they remain with their families, that they are kept out of detention centers and that their best interests are protected throughout the journey.”

While Mexico is implementing measures to safeguard children’s rights while in transit or seeking asylum in the country, challenges persist.

While Mexico is implementing measures to safeguard children’s rights while in transit or seeking asylum in the country, challenges persist. According to government statistics, more than 30,000 children from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador were temporarily held in detention centers in 2018, and so far more than 21,000 children have been detained in 2019.

UNICEF is also advocating with its government partners to build on the country’s existing successful programs for children on the move, keeping the best interests of the child above all other considerations.

Top photo: Mario from El Salvador was separated from his uncle and detained in Tapachula before UNICEF intervened and helped secure his release — allowing him to reunite with his uncle, attend school and pursue his love of drawing while waiting for his application for asylum to be processed. It took about a year but Mario and his uncle were eventually recognized as refugees by the Mexican government. They can live freely in Mexico without fear of being deported. @ Brenda Hernández for UNICEF México

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.