UNICEF Is Helping Children Driven Out of School by Violence in Africa

UNICEF and partners are working tirelessly all over the world to save and protect children.

A surge in attacks and threats of violence against students, teachers and schools — on education itself — is casting a long and foreboding shadow over children, their families, communities and society at large in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

Particularly in the countries of the Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger) and the Lake Chad Basin (Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria), ideological opposition to what is seen as Western-style education — especially for girls — is central to many of the disputes between warring factions. As a result, schoolchildren, teachers, administrators and the education infrastructure are being deliberately targeted.

The number of schools forced to close due to insecurity in conflict-affected areas of West and Central Africa tripled between the end of 2017 and June 2019. As of June 2019, 9,272 schools were closed across eight countries in the region, affecting more than 1.91 million children and nearly 44,000 teachers.

UNICEF works in many ways to keep out-of-school children learning during emergencies, including partnering with the Children's Radio Foundation to pilot an innovative radio education program, setting up temporary learning centers, supporting education authorities to upgrade teachers' skills and providing teaching and learning materials.

Above, old desks are lined up across the road on the outskirts of Banki town in northeastern Nigeria, where homes, shops and schools sit empty, deserted by families fleeing insecurity. The region has been engulfed by conflict for years. More than one quarter of the 742 verified attacks on schools globally in 2017 took place in five countries across West and Central Africa. © UNICEF/UN0322365/Kokic

"Back home I liked going to school," says Bouba, a survivor of a Boko Haram attack on his village, Mabas, in Cameroon two years ago. "I was good at maths, and I even liked doing homework. Now, when I see other children returning from school during the day, I want to be among them."

Bouba herds cows for his foster family in Baigaï, a village near the Nigerian border. The family can't afford to pay for the government documents he would need to enroll in the public school, so he attends a UNICEF-sponsored "radio school" in his spare time, sitting under the shade of a large tree in the government school courtyard with a dozen other children, some displaced like him, others too poor to pay public school fees. Together, they listen to lessons broadcast on a battery-operated radio set for two hours at a time. Facilitated by a local teacher, the radio school offers children like Bouba the chance to continue their education. © UNICEF/UN0329209/Bindra

In Dori, Burkina Faso, radio school facilitator Abdoulaye, 23, helps 14-year-old Hussaini through lessons broadcast as part of the Radio Education in Emergencies program. Since Hussaini's school was destroyed by militants and he and his family were forced to escape their village in northern Burkina Faso, he hasn't set foot in a classroom. "I used to love school, to read, to count and to play during recess," he says. "It's been a year since I last went to school." Thanks to a radio set Hussain was given as part of a pilot program, he is learning every day. "It's good. All the family listens to the lessons now." But he still misses his old school.

Abdoulaye says attacks against educators have escalated. "At first, they only threatened schools. Nowadays, they actually kill us. They are targeting the population, forcing people into displacement. As facilitators, we try to be discreet because of the security situation. If people see what we are doing, we could get killed." But he is determined to see that the next generation receives an education. "It's very important for these children to learn. They are our younger brothers and sisters. We must help them. Parents also want their children to learn, despite the risks." © UNICEF/UN0329265/Bindra

Delphine Bikajuri is principal of GEPS Youpwe, a government primary school in Douala, Cameroon. Bikajuri's daughter was kidnapped from her high school in northwestern Cameroon, along with over 150 other students. One of two English-speaking regions in Cameroon, the North West has been hit by increasing violence following protests calling for greater autonomy in the region three years ago. Non-state armed groups have declared a ban on education and imposted lockdowns, or ghost-town days, forcing people to stay in their homes and impeding delivery of humanitarian assistance. Over 80 percent of schools are closed in the North-West and South-West regions as a result of the crisis.

Bikajuri's daughter was released after two days, but abducted again by soldiers who called her and her husband traitors. The couple negotiated for their daughter's eventual release. "Some children never go back to school," she says. "How will children be leaders of tomorrow, if they are not educated?" © UNICEF/UN0329173/Bindra

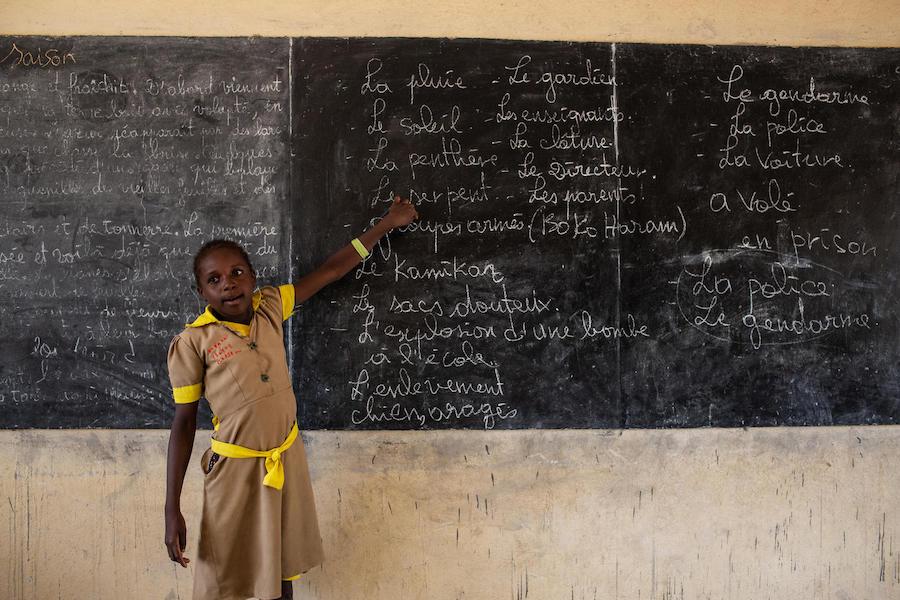

A student goes over blackboard notes for a class in emergency preparedness in case of armed attack at a school in Baigaï, a village near the Nigerian border in Cameroon's Far North region. The program focuses on teaching children and teachers what to do in the event of an armed attack on their school.

Children who are forced out of school by violence face a much higher risk of recruitment by armed groups than their in-school peers. Girls are forced into early marriage more often. Both boys and girls become easier targets for traffickers and are quicker to fall prey to abusers. © UNICEF/UN0329201/Bindra

Standing in her home in Banki, northeastern Nigeria, 13-year-old Bintu recalls the day her village was attacked by armed men four years ago. "I was going to school before the conflict started but then the insurgents came," she says. "On the day they came, I was in school in the morning and then I went home and at point they came and we ran. Everybody ran. They burnt the school down. I was so upset. I felt like my dreams would never be achieved."

Bintu and her family spent two years living with her uncle in neighboring Cameroon. Now back in Banki, Bintu is enrolled in the newly rebuilt school. "I'm so happy to be back in school because I will be educated and I'm learning something new." © UNICEF/UN0311778/Kokic

Thirty years ago, governments around the world made a historic commitment to the world's children by adopting the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which guarantees every child the right to an education. Now more than ever, governments must reaffirm their commitment to protecting education from attack and providing the resources to help their youngest citizens to keep learning, to make sure the potential of a generation of young people is not wasted.

Read the full report here: Child Alert: Education Under Threat in West and Central Africa

Top photo: On June 26, 2019, children take part in an emergency attack simulation as they practice shelter and evacuation procedures in the event of an armed attack at the Yalgho Primary School in Dori, Burkina Faso. © UNICEF/UN0329518/

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.