Using Data, Science and the Media to Fight a Pandemic

A microbiologist, a public health journalist and UNICEF's data chief discuss disease spillovers between species, a spike in domestic violence under quarantine and the race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

Since the World Health Organization was notified of the first cases of pneumonia with unknown causes in China on December 31, 2019, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide has risen to more than 3.1 million with 227,675 deaths. In response to the fast-evolving pandemic, UNICEF has revised its original emergency appeal from $42 million to $651 million. UNICEF's COVID-19 response is focused on the urgent prevention of new infections, the scale-up of alternative communication channels to keep children learning while schools are closed, supporting health systems to boost supplies of key equipment and tackling misinformation.

Below, a panel of experts — UNICEF Associate Director for Data and Analytics Mark Hereward, American Society for Microbiology Director of Global Public Health Programs Mark David Lim and Washington Post Senior Writer Frances Stead Sellers — discuss UNICEF's approach to preventing and mitigating the effects of this unprecedented global health crisis. This conversation has been edited and condensed.

So much of UNICEF's work is data-driven. How does UNICEF collect data, and how has the pandemic affected that process? How is it being analyzed?

MARK HEREWARD: One thing we can do is make good use of the massive database that we already have. You can tell a lot about the future from what we already know. We can say, "Okay the schools are closed. One of the mitigating measures is online learning." Well, what percentage of children in a country have access to the internet in the home? If it's very few, then children are going to come from every other home to join in, so we need to think of a solution. If there are a lot of adolescents on anti-retroviral treatment, we know that there is a service that may be interrupted, and if it is interrupted, it will be disastrous. We need to focus in those countries on that particular issue.

Then we can start getting speculative. We know from other studies that there is a relationship between gross domestic product and infant mortality. If we look at this unprecedented global recession that's coming up, the global GDP may go down from its projected rate. If that's true, we can say, "Well, probably that means hundreds of thousands more infants are going to die." It's rough and ready, but it's just enough to alert what we should be doing.

Then we need to ask, "What data can we collect rapidly that will inform and help refine these things and build us better models?" We have to be looking at the epidemiology. How infectious would children be? We know now that children can be infected at about the same rate as adults, but the symptoms are much, much less overall. If the symptoms are less, does that mean they're also less infectious? That governs a lot of the kinds of strategies that you want to have where you cannot have a lockdown in countries where people live hand-to-mouth every day.

Rapid data collection helps identify the needs of acutely vulnerable groups

How do you use data to determine what the strategies should be?

MARK HEREWARD: We start collecting information. How do people get food every day? Do they have savings? What will happen to the supply system? We reach out to collect from all sorts of places. We use big data where we can. For 25 years, UNICEF has been supporting the household survey system, multiple indicator cluster surveys. Those are face-to-face surveys, so the field work on those has stopped. But we can use the sampling frame from those to make phone-based surveys that can reach out to people at least for short questions about what's happening around COVID. We're looking for what can be done to rapidly collect information. It won't be as high quality, probably, but is it good enough quality to be able to make decisions?

A young child has his temperature checked as people receive food support at a program organized by the Southern Peace Media Club to help those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand's southern province of Narathiwat on April 17, 2020. © UNICEF/UNI325346/Tohlala/AFP

What are the different ways you use the data?

MARK HEREWARD: If it's data based on statistics and on quality, then we put them in our data at UNICEF.org and we make them all public. When they're a bit more speculative, when their insights come from big data, for example, rather than statistical, they need a lot of contextualization. We use this information in our discussions, in our collaborative work with other agencies, with academic institutions and, ultimately, for our country offices' collaboration with country governments to say, "Look, the data are not perfect, but they seem to indicate that we should really be concentrating here in this part of the country, or in this group of people." Groups that you may not originally think are vulnerable, like the children of frontline workers. They end up with family separation. Who's looking after the children while their caregivers are on the front lines? We need to be identifying these groups that we may not have initially thought of as vulnerable. It's a question of getting enough data to supplement and give quick insights onto the solid data that we start with.

There's never been a more pressing case for collaboration among the scientific research, governmental and other communities. What are you seeing, and do you think that if there were a breakthrough, will it be born of that collaboration?

MARK DAVID LIM: No one is spared from this crisis right now. Scientists can offer tools to help address this crisis, and they're coming together in unprecedented ways. We have to link the science with the public health delivery. It's not just about developing a vaccine, it's also making sure that vulnerable populations can access it, that it's affordable. In the geographies that we serve, these may be populations that normally don't interface with the health care system, and now we have people coming in, knocking on the door. They may not know about this virus, particularly in the more rural communities, and we have to take all that into context as we think about how we deliver the product.

In terms of the scientific community, we need to bring the microbiologists together. There's expertise that's needed to understand the human health implications. That goes into the epidemiology as well. Animal health also plays a very important role. We know using the sequencing data that this virus likely originated from a bat. We're trying to understand, is there an opportunity for early intervention before these kind of spillover events occur? How do we monitor this in the future so that we can better prepare for it?

Microbiologists "follow the bug" to learn more about how it jumped from bats to humans

Are there any historical precedents for this work?

MARK DAVID LIM: One good example that comes to mind is the Nipah virus, which also originates in bats. In Bangladesh, it was found that the transmission to humans went through date palm sap, which both bats and humans drank. Just preventing bats from accessing and defecating and putting saliva into the sap was one effective measure, but the same virus also transmits from fruit trees to livestock to humans. The only way we're finding this out is by actually following the bug. That's where microbiologists come in. Sequencing is now a term of art instead of a term of scientists. When China first shared the viral genome publicly, they confirmed that it is a virus, and data told us that it was a coronavirus. It's similar to SARS but it's definitely a different beast.

This guided public health experts to realize that quarantine, social distancing — because it's a respiratory virus —is probably going to the best non-pharmaceutical intervention. It also told us that because it originated from a spillover event, maybe we have to start looking at livestock markets. It could have hopped from bats to humans. We have to start looking at that as another possible non-pharmaceutical intervention.

That same RNA data really catalyzed a lot of our vaccine and diagnostic efforts. I think we always want to do everything yesterday, and everyone's saying "We don't have testing capacity," but really, we only discovered this virus four months ago. To have population-level screening is quite an accomplishment. Even though we don't yet have the coverage we want, I'm optimistic that we'll get there.

In April 2020, traveling by bicycle, Idress Seyawash embarked on a 25-day campaign to raise awareness on COVID-19 key prevention measures and promote handwashing among children in rural villages in Afghanistan. © UNICEF/UNI325979/

How is data being shared within the scientific community?

MARK DAVID LIM: There's a database called The Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data. There are 5,800 data sets already there. The reason sequencing's important is that it tells us how the virus is going between geographies. It's also letting us know if there's any significant mutation that may make us rethink, maybe this vaccine is no longer going to be effective. Maybe we need a new diagnostic test to stay one step ahead of how the virus changes. It all goes back to collaborations. Microbiology is an important part of that.

It's a race between the virus and our network to see who prevails. Frances, the media plays a key role in keeping the public informed. It can be very hard to divorce the pandemic from politics. What are your thoughts as a senior writer, somebody who has made these editorial judgments on reportorial and editorial page coverage?

FRANCES STEAD SELLERS: We do have to distinguish between different forms of journalism. The first kind of reporting is what I do. Reported journalism gives you the best shot at the facts, the evidence as far as we know it. We have the enormous privilege of talking to many people on the ground, talking to experts, gathering information. Then editors come after me and say, "Did you ask that question? Did you find out the other side of the thing?" It's a process that culminates in a good piece of reported journalism.

Next there's the opinion side of things. It used to be very easy to distinguish those in the old days, because the opinion belonged on the editorial pages at the back of the newspaper. Now any reputable news outlet will label them as opinion perspective analysis, so the reader can see clearly the story presents a point of view.

Then there's the third form: service journalism. If you want to know how to sew a mask, how to wash your hands, that's often where you'll find the information, and you can rely on journalists to go to the Centers for Disease Control, figure out what the best mask pattern is, and then publish it so that you can use your computer to print out your own version and make your masks. They're all very different approaches, but the goal is the same: to present the reading public with an accessible, knowledgeable form of the news, taking the difficult stuff and making it palatable and understood.

COVID-19 prevention measures affect children's access to food, education and health care

Mark, what else surprises you in the data?

MARK HEREWARD: I'm still struck by the amazing relative impunity for children from this virus. We're so used to children and old people and other vulnerable populations being the ones hardest hit. It was a real challenge to jump in and say, "So what does this mean? Is it that children are being less infected?" Which is what it seemed like to begin with, but then it turned out it was just because children were actually out and about and in areas where there were few people who were infected. Ironically, once the lockdowns happened, they were in the same environment as everybody else, and then they were getting infected at the same rates. It's clear that they get infected, but it doesn't hit them so hard.

Then, what does that mean? It puts us into a whole new moral territory, because it puts into really sharp contrast the incredibly big socioeconomic impacts on children of the preventive measures and of this global economic downturn which is a secondary effect of the lockdown measures. Compared to the disease, children are way disproportionately affected by the socioeconomic impacts. How do we balance those as a society? Each society has to ask, "Is it worth having these impacts on children to be able to mitigate the effects of the disease on, let's say, older people?"

UNICEF water, sanitation and hygiene specialist David Símon talks with women about COVID-19 prevention measures at a health clinic on the outskirts of Caracas, Venezuela on April 22, 2020. © UNICEF/UNI324990/Párraga

When stress goes up, so does violence against women and children at home

How do you balance it so the interventions have the maximum protective impact for those who need protection and the minimum effect on children's lives and futures?

MARK HEREWARD: We need the epidemiological and biological science to understand how children are affected and how infective they are when they come into contact with other people, as well as the impacts on society. What is going to be the impact of this incredible global recession on children? We know that after the 2008 financial collapse, which is small potatoes compared to this one, it was the poor countries who were hardest hit, and of course, it's the poor households within poor countries that are even harder hit. This is going to affect children's lives in a whole variety of ways: fewer resources for food, for getting children into school and keeping them in school, for using health services in so many countries.

All of this stress brings incredible pressure, which unfortunately results in violence against women and children within the home. At the same time, the social services which should be mitigating against that are also disrupted. There's a double bind that children are going to be caught in, a more or less invisible outbreak of violence. Again, we're trying to work with our data scientist friends to look at feeds from news media and social media to see if we can even get a feeling for how much violence at home is increasing. Because it for sure is. We saw what happened in Sierra Leone during the Ebola crisis: teen pregnancy rates rocketed by up to 65 percent. In one study, most girls reported this increase was a direct result of being outside the protective environment offered by schools.

We know anecdotally what's happening. We have to get better at finding the data to make a difference. We do this to find out what we can all do globally, collectively, country by country to be able to do the best by children in the world.

Vaccine development: "finding the winning horse"

What's next in terms of drug treatments and vaccine development?

MARK DAVID LIM: In other diseases, you have an idea of who may be infected but here, any of us could be carriers or transmitters. That's quite scary. In terms of product development, there is the academic research, which is very important to even just find the ideas. Then it's a laborious process to figure out which ideas can be translated to something we can access at the clinic. We have to make sure that they're safe for populations as well as effective. That's what we call the phase one clinical trials. Even if we're repurposing drugs that may be from other diseases, we don't want to shortcut safety knowing that we want to continue treating this highest risk population.

The rest is making sure it's effective. Do we even know what we're trying to do with treatment? For example, for HIV at a population level, we want to bring the viral load down to a point where it's no longer transmissible. They're not 100 percent cured; they may still have the virus. For COVID-19, is that the threshold we want to aim for, where people aren't transmitting, or are we actually trying to bring everybody down to zero? Bringing down to zero is very hard. We really need to start working together to understand and agree to what that threshold would be, and that links back to science.

When you see one spillover event, you wonder if this is going to hop over between other species. In the popular press, you see "Does your dog have it? Does your cat have it?" Those are actually serious questions, because if the reservoirs of disease where they may not be affected by the infection but they can become another host to bring it back to us, or the spillover could then hop back and forth, that becomes very dangerous from a public health level, so for prevention and treatment, we have to understand, does prevention mean also looking at livestock and wildlife? It comes back to following the bug and really understanding the nature of it. In terms of product development, there's still a lot we need to know before we can really choose what's the winning horse. We also have to put it in the context of a public health program and making sure people have access to these tools.

Ten-year-old Kolo, left, and his friend Chris, 6, wear masks and wash their hands to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Korhogo, in northern Côte d'Ivoire on April 29, 2020. © UNICEF/UNI325661/Frank Dejongh

Public health systems need consistent, robust support — not just during a crisis

How is the crisis affecting public health systems?

FRANCES STEAD SELLERS: Ultimately, public health is only as good as its messaging with politicians, policy makers and the general public. It comes back down from the very high level work that Mark Lim was talking about, to the conversational stuff that I'm talking about. Getting the message out. So often, it's a victim of its own success. Public health isn't noticed as soon as it's successful. There's a wonderful anecdote that Al Sommer, who was the Dean of the School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins used to tell about people who come out of cardiac surgery and say, "Thank God for the miracles that are being done," and give $1 million, if they're rich, to the cardiac surgeons. But nobody wakes up in the morning and says "Thank God I've got potable water," or "Thank God I don't have smallpox." Because as soon as you don't have those problems, you don't think about them.

Public health needs to be funded in a way that's consistent and successful all the time, not just when we have disasters. The situation I've written about the most is in the U.S. There are something like 3,000 public health departments in this country, all working earnestly on their own to do the right thing. Something like 100 departments in North Carolina, for example. Many of them are rural, all trying to combat this common enemy. The CDC is producing wonderful work and has had some shortcomings, but it has no authority over those health departments. It has to be invited into a state.

In fact, there's no single system of public health. It's quite a remarkable thing to discover. The country also spends something like $19 per capita every year on public health, whereas in terms of treatment, it's about $11,000 per capita spent every year on an individual, so public health doctors will tell us we have an illness or a treatment system and not a health system in this country.

I think it's only now when a disaster happens that people begin to understand that public health even exists. They thing of it as something that happens in schools of public health, and there are very, very famous ones here like Hopkins and Harvard and Columbia, and there's remarkable research going on, but there are also these departments that are working very hard to track measles outbreaks. They're dealing with maternal health issues. They combat all of these issues with a population-wide approach instead of the individual health treatment approach that is so wanted in this country.

To learn more about how UNICEF uses data to inform the COVID-19 response, see the interactive data visualizations containing the latest information from UNICEF's global databases.

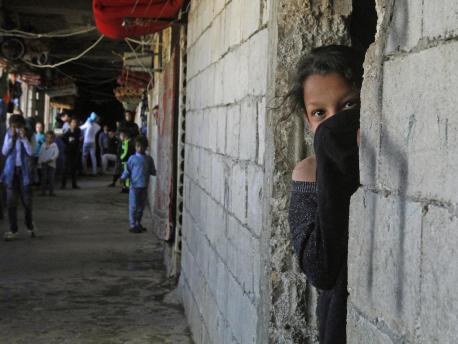

Top photo: On March 17, 2020, a Syrian refugee, her face covered to protect against COVID-19, looks out from a doorway in an unfinished building where she and her family have been living in the city of Sidon in southern Lebanon. © UNICEF/UNI317859/Zayyat/AFP

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.