"We Are Americans. We Were Raised Here." A DACA Recipient's Story

DACA recipients breathed a sigh of relief when the Supreme Court ruled in their favor on June 18, but they are still living in limbo. UNICEF USA's Giovana Ortiz-Barrera, herself a Dreamer, shares her story.

UPDATED JULY 9, 2020 — As a UNICEF USA community engagement associate, Giovana Ortiz-Barrera empowers grassroots volunteers and leaders to educate, advocate and fundraise in support of UNICEF's work to save and protect vulnerable children around the world.

The Clark University graduate is also a Dreamer, one of 1.4 million young people brought here as children and raised in the United States. Some 700,000 Dreamers are currently protected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy better known as DACA. Adopted in 2012, the policy shields young undocumented immigrants from deportation and allows them to get a driver's license, attend college and build lives and careers in the only home they've ever known.

On June 18, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the Administration may not proceed with its 2017 decision to terminate the DACA program, protecting the Dreamers — for now. "It felt good, for a moment, but it's very temporary, because it's not a permanent fix," says Ortiz-Barrera. "So it didn't feel as good as it should have. It's a constant limbo, with ebbs and flows of scares." The House of Representatives has passed legislation that would allow Dreamers to remain in the U.S. and offers a pathway to citizenship. Now it's the Senate's turn to act.

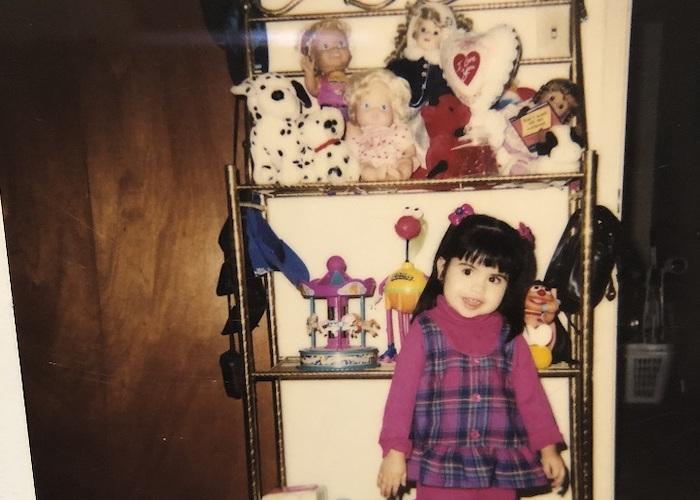

UNICEF USA Community Engagement Associate Giovana Ortiz-Barrera was 2 years old when she and her mother left Jalisco, Mexico to join her father in Atlanta. © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

Can you tell us about your background and how you came to work for UNICEF?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: I am an immigrant from Mexico, raised in the U.S. by immigrant parents. Growing up in the States, I faced some challenges that I thought weren't necessarily unique to my experience but later, when I went to college and started learning more about development work and refugee experiences, I realized that my experiences were unique to my status and to socioeconomic factors outside of my family's and my control.

I realized that my experiences were unique to my status and to socioeconomic factors outside of my family's and my control. That's when I began to take more interest in development work. I dreamed of working for an organization like UNICEF, that works to protect children and put children first.

That's when I began to take more interest in development work. I dreamed of working for an organization like UNICEF, that works to protect children and put children first, especially children who have been affected by such factors that influence much of their daily experiences.

Why did your parents immigrate to the United States?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: My parents brought me over when I was just 2 years old, from Jalisco, Mexico. They are both from Jalisco and they grew up in the city. Their parents are from rural areas of Jalisco. They faced some challenges with their family not having enough food or the financial resources they needed to get an education. For example, my dad's parents were only able to afford to pay for him to go to middle school. After that, he started working because he had to help support his family. It was the same for my mother. When they got married and had me, they realized that the opportunities they had weren't enough to help a family grow and do well in that state and in Mexico at that time.

They had family who migrated to the U.S. back in the 80s when there was immigration amnesty during the Reagan era, so they were able to get in contact with those family members who said, "There are opportunities for you here. You'll be able to help your family and have a better life." That's exactly what my dad did. He was the first to come to the United States and meet with family in Georgia. After a couple years, once he was settled in Atlanta, he sent for my mother and me. That's when my mother and I began our life in the U.S.

Giovana Ortiz-Barrera grew up in Atlanta. Her parents worked multiple jobs to support her and her two younger siblings. "My parents [told] me they didn't want me to work the jobs that they were working. They wanted a better life for us." © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

What were some of the challenges of acclimating to life in the U.S.?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: I remember when I started Pre-K, I didn't speak any English. My parents didn't know any English either, so they raised me speaking only Spanish up to 4 or 5 years old. Going into school, it was very difficult for me to communicate with teachers and other students.

I didn't even know that I was undocumented — or what that meant — until junior year of high school.

But throughout my elementary school years, it was also a very difficult time for my parents, just understanding that they needed to learn the language in order to actually survive, to attend doctor's appointments, to get the proper care they needed. That's when my dad really started to study the language. He was able to learn it a lot quicker that my mother because of his job.

Did your parents tell you about your immigration status when you were a child?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: I didn't even know I was undocumented — or what that meant — until junior year of high school. I became a DACA recipient in 2013. They started accepting applications from young people who didn't have legal status, so that we could receive a renewable work permit, to become eligible to not only attend school but to legally work within the U.S. and pay taxes and [have access to] all of the things that usually come with a Social Security number.

Giovana Ortiz-Barrera was a junior in high school when she learned about her undocumented status. She became a DACA recipient in 2013. © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

Was it hard to navigate the DACA application process?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: It was very difficult for my family when the policy came out, because none of us had really ever gone through any immigration process like this. We were almost in disbelief, trying to understand what this meant for me and my family members going forward. We weren't familiar with any of the legal jargon that was being used. We were really afraid of not going through the process correctly and having that later affect my ability to apply for this status.

We started by finding a lawyer, who asked for a ton of documentation... anything that could provide evidence that I had been living here and that my parents had been supporting me for 16+ years.

We started by finding a lawyer, who asked for a ton of documentation — immunization records, pediatrician records, tax records, anything that could provide evidence that I had been living here and that my parents had been supporting me for 16+ years from when I was brought over. That took a lot of digging and contacting the IRS and getting all kinds of information for the lawyer to present with my application so that it would go through.

It was also a financial burden on my family. I recognize that I do have privilege in the fact that I can actually get employment legally, but for [undocumented] immigrants in general, it's very difficult to get good paying jobs. I have two younger siblings and my parents have a lot of expenses. Hiring a lawyer was quite expensive — $2,000 just for the lawyer's services. In addition to that, the application itself was $465. That was a lot of money for my family to pay right away.

Giovana Ortiz-Barrera (center) attended public school in Atlanta. "When I was in middle school, some students would ask, 'Are you illegal?' because they knew I was from Mexico. 'Oh, are you a wetback? You're an alien.' That really hurt." © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

When did you discover that you didn't have a Social Security number?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: What I had used for schooling and things like that up to high school was my tax ID, which was fine back then. But people started asking, "Do you have anything other than your tax ID?" That's when I learned that I didn't have a Social Security number or anything that could show that I was legally residing in the U.S. I realized that I couldn't apply to college. It was so emotional for me because my whole life, I had been raised with my parents telling me they didn't want me to work the jobs that they were working. They wanted a better life for us.

When I faced this barrier of not being eligible to apply for college or get financial aid to go to college, I felt like a disappointment to my family.

Growing up, they would tell me that if I worked hard in school and did really well, then I would become a really successful person and I would help the family. My parents were always so proud of me for having good grades and things like that. So when I faced this barrier of not being eligible to apply for college or get financial aid to go to college, I felt like a disappointment to my family.

I went into this dark hole and became depressed and didn't know what to do. I think I tried to hide things from my parents, but they know me and they handled the situation really well.

A cheerleader in middle school, Giovana Ortiz-Barrera now organizes grassroots volunteers and leaders to educate, advocate and fundraise in support of UNICEF's work to save and protect vulnerable children around the world. © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

How did you feel after you became a DACA recipient?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: I didn't really question these policies until after I started learning more about them through my liberal arts education. Back then, I was so ecstatic simply to have the ability to apply to all of the schools in the Northeast that my college counselor recommended and found that would help me, especially with my status. Back then, it felt like a fix, but years later when politicians started talking more about DACA policy, I realized that it wasn't a good fix. It was more like a Band-Aid to this problem.

When politicians started talking more about DACA policy, I realized that it wasn't a good fix. It was more like a Band-Aid to this problem.... I am grateful for all that it gave me, but there are so many things that are wrong with the policy.

I have to apply for this every two years and again pay that fee, which has gone up to $495. I've had to go through that nerve-racking and anxiety-inducing process. This applies to a lot of my friends too. It's a big burden for our families. If there are any inconsistencies between our previous applications and the new one, our status is in jeopardy. I am grateful for all that it gave me, but there are so many things that are wrong with the policy. My whole tuition came from my father's life savings.

What would happen to you if DACA was phased out?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: When people started talking about that back in 2015, 2016, to be completely honest, it felt like a slap in the face. Getting into college and being so close to graduation, my friends who were DACA recipients and I were furious and frustrated. That would mean we couldn't go on to get a job after receiving a degree. Our parents worked so hard — two, sometimes three jobs just to fund our education. It felt unreal. We had thought things couldn't get worse, it could only get better. It just felt like all our hopes that we could support our families in the future were gone.

Giovana Ortiz-Barrera (second from left) and classmates at their high school graduation. © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

You must have felt like the rug was being pulled out from under you. How does it make you feel when people use terms like "illegal immigrant" or "alien"?

GIOVANA ORTIZ-BARRERA: When I was in middle school, some students would ask, "Are you illegal?" Because they knew I was from Mexico. "Oh, are you a wetback? You're an alien." That really hurt.

It's sad, but I wasn't proud of my Mexican background then, because I knew what questions would come with me saying that I was Mexican. I guess later when I started speaking up about DACA and about my undocumented status, I had a bit of an identity crisis because I had never really been proud of who I was.

When did you become more comfortable about sharing your heritage and speaking out about your story?

GIOVANNA ORTIZ-BARRERA: I think it was around sophomore year in college, 2015. I realized that I wasn't alone. I found others at my school who had the same status. Even with one another, we didn't necessarily introduce ourselves that way. After building relationships and friendships, we began to learn certain things that led us to ask, "Hey, are you by any chance a DACA recipient?"

We began to build a community within our university where we were one another's support going through it all. The situation was really new for schools, too. Even applying, the international students' office wasn't really familiar with our status. They had heard of it, but they didn't have the systems in place to support us. We couldn't be categorized as citizen or permanent resident or international student because we weren't any one of those things. We are Americans. We were raised here but we come from different backgrounds, different heritages.

We couldn't be categorized as citizen or permanent resident or international student because we weren't any one of those things. We are Americans. We were raised here but we come from different backgrounds, different heritages.

I guess it was going through all of those experiences that really empowered me to speak up about making sure we had the resources in place, not only at school but for health services and mental health, to help us get through everything that we had been experiencing, in addition to being first generation students at a private university. That's when I became a little more vocal and I realized that I should be proud of who I am and where my parents come from.

Even now, when people ask, "Where are you from?" I always say, "Mexico, and I'm proud of it."

Top photo: From left: Giovana Ortiz-Barrera — now a UNICEF USA Community Engagement Associate based in Boston — and classmates celebrate their graduation from Clark University in 2017. © Giovana Ortiz-Barrera

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.