After Two Years in Limbo, Rohingya Children Crave the Chance To Learn

The youngest victims of Myanmar's ethnic cleansing campaign are missing out on what only education can offer: a chance for a brighter future.

UNICEF and partners are working tirelessly all over the world to save and protect children.

For the past two years, children in the overcrowded Bangladeshi camps where 900,000 stateless Rohingya refugees now live have had precious little time to do what kids normally like to do. Twelve-year-old Mohsina stays home to take care of her housebound father who lost his leg after he was shot by the Myanmar army. Rashed, whose father says he has the mind of an engineer, is the one who installed the solar panels that bring light to his family's shelter. Without 7-year-old Kafayet's help, his family would not eat.

“Every day I walk around the camp collecting plastic bottles to sell to the recyclers,” says the boy, who has logged a mere 15 days in school throughout his life. “My family uses the money to buy fish and vegetables.”

Life in the camps is harsh, and survival requires everyone to pitch in. But as the Rohingya refugee crisis enters its third year, children who've developed survival skills well beyond their years crave a different kind of challenge. They yearn for the stimulation and promise that only education can bring.

I studied six subjects back in Myanmar,” says Abdullah, 18. “But when I arrived here, there was no way I could continue. If we do not get education in the camps, I think our situation is going to be dire.

“I studied six subjects back in Myanmar,” said Abdullah, 18, who lives in the Kutupalong refugee camp. “But when I arrived here, there was no way I could continue. If we do not get education in the camps, I think our situation is going to be dire.”

When Rohingya refugees from neighboring Myanmar began streaming into Bangladesh in 2017, fleeing an army-led offensive, UNICEF and partners immediately set about giving children a chance to learn. In Myanmar, most Rohingya have no legal identity or citizenship. And while Bangladesh gave them safe harbor, they remained minorities with no legal status, and their children were barred from receiving any formal education.

UNICEF and partners established centers where the kids, many of whom had never set foot in a classroom before, could begin to learn. As of today, over 2,500 centers are up and running, serving nearly 200,000 children.

Girls vie to answer a question in class at a UNICEF learning space in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.© UNICEF/UN0326969/Brown

“In the beginning, without materials or a curriculum framework of any kind, learning centers were mostly about play and drawing,” says Charles Avelino, Education Manager with UNICEF Cox’s Bazar Field Office. To add substance, UNICEF and partners developed learning materials and trained instructors — a mix of local Bangladeshi and refugee recruits – to use the curriculum and assess their students. “Now we have turned a corner," continues Avelino. "We’re starting to put in place competency-based learning, starting with the lower grade levels. This marks a qualitative jump towards the kind of education these children need.”

Though the future of education in the camps is looking brighter, the present remains bleak for far too many children, and significant challenges remain.

Rohingya children at a safe space for women and girls in the Moinarghona refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. Traffickers offering to smuggle desperate young Rohingya out of Bangladesh and drug dealers who operate in the area have made the camps dangerous places. Women and girls face harassment and abuse especially at nighttime. © UNICEF/UN0334323/Chak

Around one-third of Rohingya children between the ages of 4 and 14 are missing out on education. To meet their needs, UNICEF is exploring such options as home-based learning for younger children. But there are still no secondary schools for teens who live in the camps, a void that leaves parents rightly concerned. The longer their children go without education, the greater the risk they will fall prey to exploitation and abuse.

Education takes people from the darkness and brings them into the light.

“Educated people have a value wherever they are,” says Mohamed Hussein, who sends two of his children to a learning center. “Whether my son goes back to Myanmar or to Malaysia or anywhere else, the same is true.”

Teenage boys are among the most disaffected. The vast majority are out of school and don't attend any of the training classes designed to help them develop marketable skills. Many spend their days entirely at loose ends, roaming the camps’ roads and walkways, where they can easily stumble into danger, especially at night.

“People in the camps are always trying to sell [methamphetamine] to me,” says Abdul, a 14-year-old who enjoyed school until he and his teacher had a disagreement and he stopped going. “They try to convince me that if I sell drugs I can make money and buy more things for my family.”

There are 100 UNICEF-supported adolescent clubs and youth centers in Bangladesh where teens like Abdul Karim (second from right) and his friends can get counseling and emotional support and take math and reading classes. Designed to equip young people for a productive future, the centers also provide vocational and life skills training.© UNICEF/Sujan

To keep kids like Abdul from falling through the ever-widening cracks, UNICEF has helped open 100 adolescent clubs and youth centers.

“Our aim is to help equip adolescents with the skills they need to deal with the many risks they encounter, such as trafficking, abuse, and — in the case of girls — child marriage,” says UNICEF Bangladesh Representative Tomoo Hozumi. “In broader terms, we are helping this generation of youth build their identity, and making them part of the solution to the difficult situation they find themselves in.”

That approach is working for 15-year-old Yasmin Ara, who thanks to UNICEF and partners is learning much more than the skills traditionally considered "women’s work." Tailoring and embroidery classes are offered at the youth center she attends, but that's not all. She's also learning the electrical skills needed to install and repair the solar panels that are common throughout the camps.

15-year-old Yasmin Ara has been attending classes at a UNICEF-supported adolescent center for the past four months. © UNICEF/UN0326954/Brown

At first, Yasmin’s parents were reluctant to send her to the center. Once girls enter puberty, many mothers and fathers believe their daughters should remain at home. But thanks to a facilitator who helped them get over their squeamishness, they are now on board. “They can see the progress I have made, they are happy for me to come here,” says Yasmin.

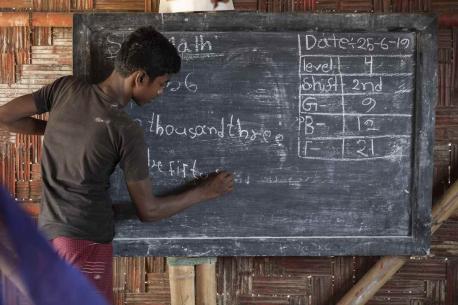

Top photo: A student works at the blackboard in a UNICEF-supported learning center in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Working with Rohingya children is inspiring to instructor Rozina Akta (not shown): "Education takes people from the darkness and brings them into the light." © UNICEF/UN0326953/Brown

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.