In Venezuela, Hero Teachers Are Determined To Keep Kids in School

UNICEF is helping dedicated teachers make sure their students get an education in Venezuela, where daily life is more difficult than ever.

UNICEF and partners are working tirelessly all over the world to save and protect children.

Deteriorating conditions in Venezuela have left some 3.2 million children in need humanitarian assistance. UNICEF is working with partners to ramp up work to help children and families struggling with food shortages and limited access to essential services like health care, safe water and education. UNICEF’s Back to School program in Venezuela is helping students thrive, but that work wouldn't be possible without the support of the country's teachers. Below, two dedicated professionals share their stories:

Lilibeth Aular and Laura Albarrán both awake with the first rays of dawn, shortly before 6 AM. One lives in Baruta, near Caracas, and the other in Maracaibo, Venezuela.

They immediately go to the kitchen to see if the water-supply cuts have been suspended or if they should go to their reserve jugs for water to drink and clean. In the past year, the latter has almost always happened.

Chronic shortages have become a way of life in Venezuela

The two have a schedule: They must get ready to teach — the morning shift for adolescents and the afternoon shift for elementary school children.

Their parallel stories, more filled with daily difficulties than dramatic events, seem to them run-of-the-mill. However, they — and all teachers — are crucial to delivering education in Venezuela, and for children in the country to continue their training. I tell them they are heroines. They are embarrassed for a moment, but then they smile and nod. They know that it is so.

Teacher Laura Albarrán at home with her children, 10-year-old Valeria and 8-year-old Manuel, in Maracaibo, Venezuela in September 2019. “I work to see these children happy,” says Albarrán. © UNICEF/UN0344404/Orozco

Aular tells me about her morning journey with a determined tone: There is little public transportation and that is why it is hard for her to get to her first job, at a school in El Hatillo, on time. Even harder is to take three different means of transport to arrive on time for her second job, at Municipal School Jermán Ubaldo Lira in Baruta, before 1 PM. “They are only difficulties. The limitations are mental,” she says.

The deteriorating situation has left an estimated 1 million students out of school

With no other option due to lack of fuel, Albarrán is forced to walk from home with her two sleepy children, Valeria, 10, and Manuel, 8, right after breakfast. Due to electricity shortages, the children sleep little in the heat and feel tired, so she takes them with her rather than leaving them at home, especially because the temperatures in her home exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

She leaves them at their grandma’s house, goes to work and leaves at the same time as Aular: 11:45 AM. In her case, she picks up her children, takes them home, makes lunch and takes them immediately to the Fe y Alegría Manzanillo School, after a 25-minute walk in the sun. Both children spend barely three hours in school due to the shortage of public services.

At Fe y Alegría Manzanillo School in Maracaibo, Venezuela, Manuel, 8, shares a drawing of his ideal classroom, stocked with "trampolines, costumes and computers." All the school's digital equipment was stolen. Electricity shortages made him add something else to his drawing a few minutes after this photo was taken: an air conditioner. © UNICEF/UN0344401/Orozco

The teachers don’t emphasize these daily details. Their only complaint is that they receive low salaries from their two jobs, less than $5 per month, and both must depend on the support of their partners. Their real concerns revolve around the children they work with. “I want the best for children,” says Aular. “I work to see these children happy,” says Albarrán. Taking care of children is their calling.

In the next 12 months, UNICEF and national partners plan to reach 1.2 million students across the country with educational supplies

But there are other reasons. More than ever, they want classrooms to stop emptying as a result of school drop-out in Venezuela. Aular estimates that "at least 30 percent of the children have dropped out in my classrooms.” Isis Roo, another teacher from Maracaibo, tells me that in her son’s class in 2018, 33 students started and only 27 finished.

Luis, 9, rushes home to show his mother the UNICEF backpack he received on the first day of class at the Municipal School Jermán Ubaldo Lira in Baruta, Venezuela, where water and electricity shortages are a constant problem. © UNICEF/UN0344478/Orozco

UNICEF supports the work of these teachers (and many others) by distributing classroom Recreation kits, Early Childhood Development kits to encourage interaction with the little ones and Back-to-School kits filled with basic school materials for students. These additional work tools help provide a reason to continue.

“I keep betting on my country. Teaching is a pillar of society. We don’t have the importance we deserve, but we give it our all because we want our children to have a future,” insists Aular, who has been working with children for 22 years, 13 of them in educational institutions. Her attitude fills me with energy.

I keep betting on my country," says teacher Lilibeth Aular. "Teaching is a pillar of society. We don't have the importance we deserve, but we give it our all because we want our children to have a future.

Albarrán considers her work heroic: “We have to teach in schools where the computers have been stolen and neither power nor water arrive. We have had to reduce the school day so that children do not go home late, for safety. My own children, when the power goes out, have to sleep on the patio because of the intense heat.”

Twenty years ago, Albarrán was a student in the same school her children now attend. Things have changed: She lets them rest one day each week to recover from sleepless nights.

UNICEF Education Officer Dario Moreno high-fives Yeiberling, 9, after giving her a Back-to-School kit in Baruta, Venezuela. © UNICEF/UN0344476/Prieto

Aular shares two other problems that she considers fundamental: Venezuela's economic crisis has led many teachers to migrate while others have resigned from their positions. “But also many children have lost their parents and now will grow up with their grandparents,” she notes.

Despite all the difficulties, she remains dedicated to her profession — and her country. “I went to Cartagena, Colombia, on my last vacation and I really needed my people and my surroundings. I get tired of belittling teaching. Sometimes I would like to quit everything, but I keep betting on teaching in my country. ”

Students at the Municipal School Jermán Ubaldo Lira in Baruta, Venezuela received UNICEF backpacks full of school supplies on the first day of class. UNICEF is providing more than 300,000 children in Venezuela with Back-to-School kits to help them keep learning amidst difficult socioeconomic conditions. © UNICEF/UN0344454/Prieto

“There are many who stop teaching class to save transportation fares, and we understand them. But those who come to teach and take time because they want to educate are heroes,” says Yaini Ulasio, an educational psychologist.

The emergency situation we live in is no secret to anyone," says teaching coordinator Nereida Goberira. "But thanks to UNICEF and the support of the office, we keep moving forward.

In fact, during the delivery of Back-to-School kits, teachers show up to help. Ulasio's face reflects her gratitude and resolve. “The children are happy,” she tells me. “The more ease they have, the more they are excited to study.”

A pilot school feeding program supported by UNICEF provides students enrolled in 24 schools in Venezuela's Miranda Province with a balanced meal. © UNICEF/UN0344472/Prieto

Nereida Goberira, a teaching coordinator at Fe y Alegría Manzanillo, has been teaching for 26 years. “The emergency situation we live in is no secret to anyone," she explains. "The shortage of money for staff and student transfers, food shortages and the high cost of living have influenced the decision to go to school. But thanks to UNICEF and the support of the office, we keep moving forward.”

Enrique Patiño is a Communication Consultant at UNICEF’s Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office.

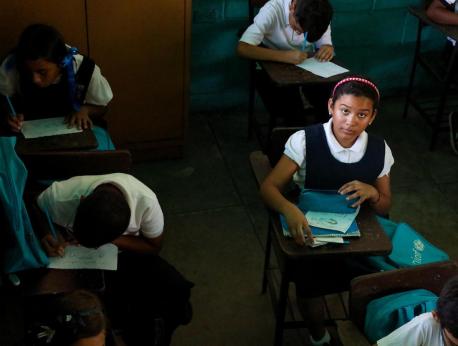

Top photo: Valeria, 10, goes to school in the afternoons only in Maracaibo, Venezuela. Power shortages have forced teachers to shorten the school day at the UNICEF-supported school, Fe y Alegría Manzanillo, so children can avoid blackouts and extreme heat inside the classrooms. © UNICEF/UN0344398/Orozco

HOW TO HELP

There are many ways to make a difference

War, famine, poverty, natural disasters — threats to the world's children keep coming. But UNICEF won't stop working to keep children healthy and safe.

UNICEF works in over 190 countries and territories — more places than any other children's organization. UNICEF has the world's largest humanitarian warehouse and, when disaster strikes, can get supplies almost anywhere within 72 hours. Constantly innovating, always advocating for a better world for children, UNICEF works to ensure that every child can grow up healthy, educated, protected and respected.

Would you like to help give all children the opportunity to reach their full potential? There are many ways to get involved.